Classroom structure is a good thing.

Patall et al. (in press) conducted two meta-analyses that showed classroom structure benefits student achievement, engagement, and competence beliefs.

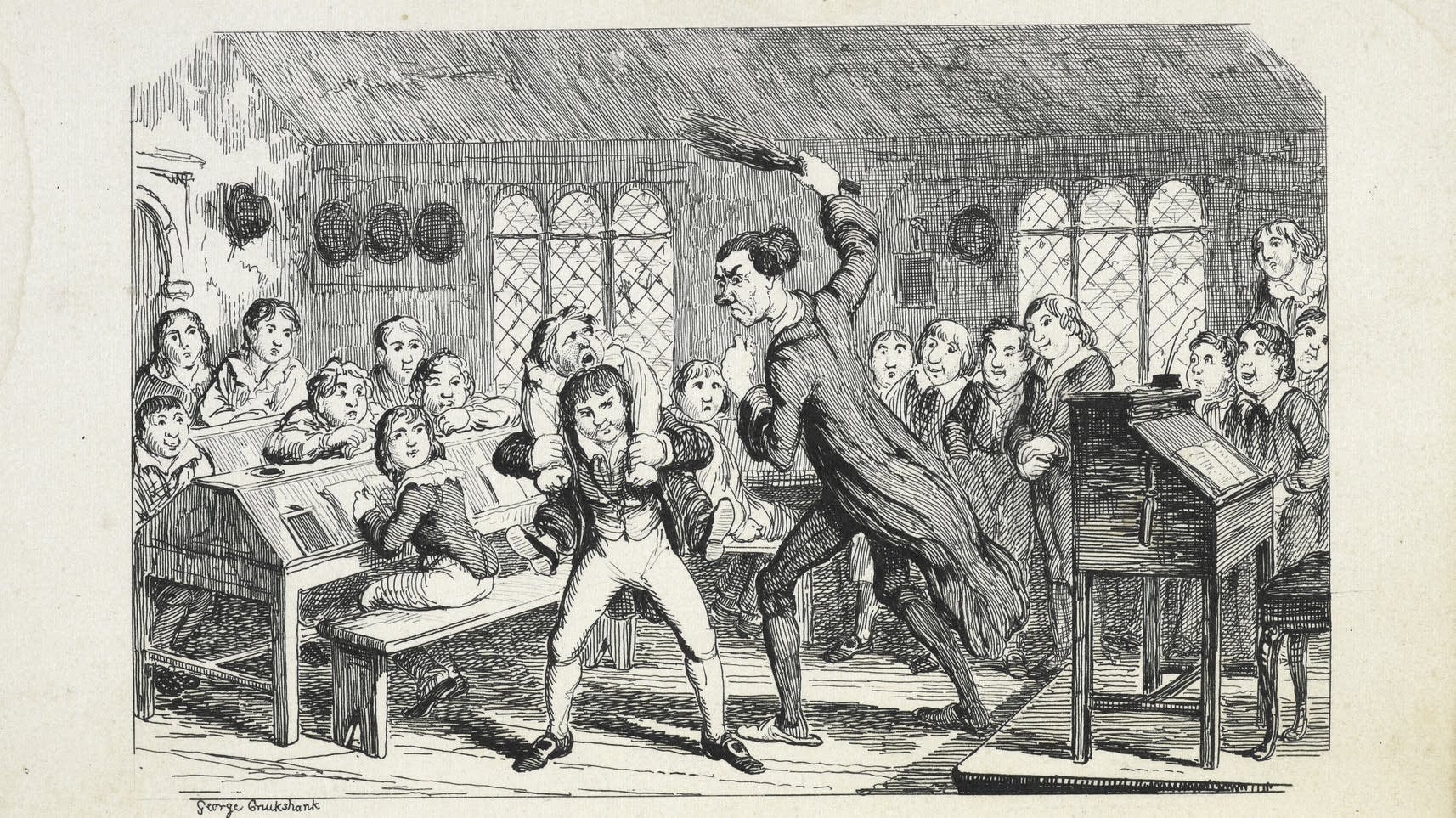

Early career teachers are taught to provide their students with a clear classroom structure - but what does that mean? Well, I don’t think anybody wants to return to the days when “structure” meant “discipline”:

That’s clearly the wrong kind of “structure.” At the same time, few students do well with absolutely no structure or guidance regarding classroom norms and expectations. A productive middle space for classroom structure is possible, and beneficial for students. Patall and colleagues (in press)1 have just published two meta-analyses that support the creation of productive classroom structure.

The first meta-analysis, examining non-experimental studies, showed that productive classroom structure is associated with higher academic achievement, more (and more types of) engagement, and students with stronger beliefs in their own competence. The second meta-analysis, focused on intervention studies involving training teachers how to enact productive classroom structure, also showed that students in classes with those teachers performed better and were more engaged. And these findings seem consistent across grade levels, somewhat surprisingly. So what does this mean for teaching?

Well, I think these meta-analyses provide further support for, as Patall et al. put it: “creating a predictable classroom environment…” that includes “…an assortment of practices implemented by teachers meant to organize and guide students’ school-relevant behavior and in turn, support students in effectively navigating the learning environment and accomplishing desired outcomes” (p. 3). These practices include supporting students’ sense of autonomy and feelings of connection with the teacher, characterized by relationship building and respect. So, think about co-created classroom norms, clear teacher expectations of students, legitimate opportunities for students to make choices about what/how they learn (within reason), and a sense of care and support. In such a classroom, there’s little need for “discipline.”

And I suspect these ideas can be applied to the workplace, also. Good leaders support autonomy, show respect and care, and provide the structure for their employees to be successful.

Full disclosure: this article has been published in the journal Educational Psychologist, for which I am a co-editor. ↩